The most visible part of South County Hospital is the stately brick building at 100 Kenyon Avenue and the land on which it rests.

The most visible part of South County Hospital is the stately brick building at 100 Kenyon Avenue and the land on which it rests.

It's hard to imagine today, but the sprawling hospital campus was once home to a farm – the Town Farm to be precise - a municipal refuge for the indigent.

In his 1973 memoir “I Remember,” James E. Perry sketched out the details of that poor farm: the “large herd of dairy cows,” the view of Ram Point (then called Hen House Point), and the vegetable garden.

“As the town grew, the need for such a facility diminished, and it was eventually closed, with most of the property sold for house lots, with the exception of the land deeded to South County Hospital,” he wrote.

For a time, however, the farm and the hospital coexisted.

Brenda (Burton) Bolster of Wakefield, who grew up across the street, remembers farmer Sonny Kenyon coming to fetch her on his tractor in the 1950s. The goats were at it again – climbing the ivy that lined the hospital's brick exterior to reach the fire escape.

If you were inside the hospital, this could be startling. “All of a sudden the nurses would see the goats on the window sill,” recalled Bolster, who would help Kenyon pull down the ivy.

Construction of Route 1 in 1962 divided the town farm parcel, with the town of South Kingstown retaining ownership of land where it built a new police station two years later, as well as two ballfields north of the highway and Marina Park south of it.

Although several additions to the hospital were built during the 20th century, by the early 1980s the hospital was bursting at the seams. In 1983 hospital officials petitioned the town for more land. They sought six acres, including the so-called upper ballfield, and offered the town a seven-year grace period to continue using it.

To appease town officials concerned about this loss of recreational land, hospital officials made an unusual offer: a land swap that would net the town 65 acres in Tuckertown to build a new park.

In April 1983, after much press coverage and some dissent, voters approved the deal. South County Hospital paid the town $175,000 for the six acres and an additional $50,000 to replace the ballfield.

The town, in turn, supplemented that $225,000 with $25,000 from an existing land acquisition fund, and used it to buy the land on Tuckertown Road.

In hindsight, Tuckertown Park – with its tennis courts, soccer fields, baseball diamond, and playground – would become the jewel of the town's recreational properties, far outshining the small ballfield it replaced. But in 1983 it was only a concept, and nervous neighbors and some cautious town officials weren't sure about the deal.

Growing beyond the Hospital

Not all of South County Hospital's growth has occurred on its Kenyon Avenue campus. Its parent organization, South County Health, has Medical and Wellness Centers in East Greenwich and Westerly, along with South County Home Health that provides patient care at home, and South County Surgical Supply, the retail entity that sells medical equipment and durable home goods.

The hospital's first off-site venture was the North Kingstown Treatment Center, which opened after the Navy pulled out of Quonset Point in 1974 and the small hospital on base closed.

Owned originally by a group of physicians, the Treatment Center started in 1976 as a clinic in a former Ground Round restaurant, according to former hospital trustee Rudi Hempe, who served with hospital treasurer Ben Sturges on a committee planning the facility.

Although Sturges was the hospital's treasurer, he served on the committee because he was a North Kingstown town councilman and lived in Saunderstown. Eventually, in 1985, the hospital acquired the Treatment Center. It is now housed in a new building on Route 2 in East Greenwich.

A new name

In the past, population growth drove the hospital's expansion. The post-World War II baby boom, South County's development explosion in the 1980s and a baby boomlet shortly thereafter, increased demand for hospital services and led to additions in 1952 (the Hazard Wing), 1962, 1970 (Borda Wing), 1980-82 (Read), 1998 (Medical Office Building) and 2007 (Frost Family Pavilion).

With the reach of services extending beyond the bricks and mortar of South County Hospital, at the June 29, 2015 meeting of the Board of Trustees, it was voted to change the official name of the organization from South County Hospital Healthcare System to South County Health.

In a press release, the reasoning behind the name change was given: “The old system name was hospital-centric, long, and bureaucratic sounding. We believe the new name better reflects the reason we are here as well as our interactions with the community - more than half of which happen outside the walls of this hospital.”

In 2016, South County Health continued its growth beyond the walls of the hospital with a satellite center on Route 1 in Westerly. The 30,000-square-foot Medical and Wellness Center gained instant popularity with residents of Westerly and surrounding communities who are served by diagnostic imaging; doctor's offices, including primary care, orthopedics and obstetrics; and an Express Care walk-in clinic, close to where they live.

The next 100 years

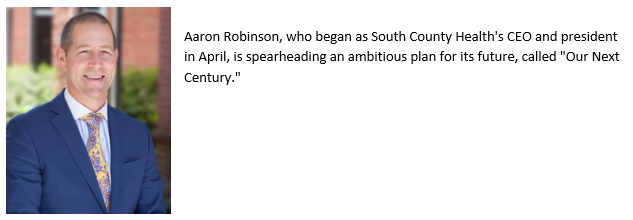

As South County Health celebrated its Centennial Year in 2019, Aaron Robinson was named president/CEO, replacing Lou Giancola who retired after an 18 year career in that role. Robinson, who led healthcare systems in other states, recognizes the potential that South County Health has to expand its capabilities and plans to respond to those changes.

“The nation is aging. Rhode Island is aging faster than the nation, and our service area is aging faster than Rhode Island,” Robinson noted. “So the shift to the senior demographic is disproportionately higher for the communities we serve.”

Under Robinson's guidance, the organization is developing a strategic plan, dubbed the “Next Century” strategy, which proposes a series of initiatives, only some of which involve physical growth. The plan was presented to the Board of Trustees in September.

Within that plan is a multi-million-dollar investment in digital technology for consideration. This would potentially solve the problem of incompatible computer programs, in addition to improving the delivery of care.

“There are inefficiencies in physicians and nurses attempting to navigate and document in multiple systems,” Robinson said. “It's almost an incalculable efficiency that you gain from an integrated system, but it is substantial, and it is the best opportunity to integrate care across the continuum for our patients.”

Other strategies include determining which areas should be targeted for expansion, such as cardiovascular services, digestive health, and oncology. South County Health is also building on its investment in robotic technology with the Institute for Robotic Surgery. Besides the latest robotic technology used in orthopedic, urologic, and general surgeries, Robinson anticipates South County Hospital serving as a beta center for new robotic technology as it is introduced.

“We have been uniquely progressive in the state for our size and scale,” Robinson said of its robotics program. “We have more robots than any hospital in Rhode Island and in certain areas like orthopedic joint replacement, South County Hospital is the global leader in robotic surgery case volume.”

The relationships that South County Health developed with industry partners such as Mako manufacturer Stryker, will help it continue to be on the cutting edge of robotic surgery, he added.

There are limits to the hospital's mission, however. It is a small facility that does not aspire to be a Level I trauma center like Rhode Island Hospital, or a site for organ or bone marrow transplants.

Ask any South County Health employee about the future of their organization and you're likely to hear optimism but also trepidation related to uncertainty in the Rhode Island healthcare market.

Optimism, because the hospital and its satellites have retained exceptional service and a family feel despite their growth. Trepidation, because the world of health care is so precarious.

Political debates about how to pay for care; the rising costs of such care; and consolidation of surrounding hospitals raise questions about where South County Health sees its future.

“I like the hospital as it is,” said Shawn Bell, a respiratory therapist who started at the hospital as an intern in 1979. “I personally don't want to merge. But we have to look at where the country's going, where medicine is going. We may not have a choice in the future. If we can stay afloat, it would be great to stay independent.”

Registered Nurse Bobbie Fay, director of critical care and cardiopulmonary services, has worked at the hospital off and on since 1971.

“It's a little nerve-wracking,” she said of the future. “We're the only hospital that's independent and you do worry about merging with another group because you don't know what they'll do to change it. We do such a good job here that you hate to lose any of that. I'm hoping that we continue as we are.”

Robinson, for his part, recognizes the challenges but is optimistic. Despite what he calls the hospital's “headwinds” - a difficult regulatory environment and low Medicare reimbursements – he believes South County Health can retain its independence and become more cost-efficient without losing its heart.

“One thing that always encourages me about South County Health is its culture,” he said, describing it as having a foundation of collaboration, collegiality, teamwork, and partnership. “Folks work well together, and they have a pride in what they do, and I think they take pride in rising to challenges put in front of them.”

A speed boat among ships

As for surrounding hospitals, all of which belong to larger organizations, Robinson is not worried.

“I think our independence can be viewed as a negative by some. It can be seen as risky in this massive rush to consolidation, but I would say also I see it as a huge strength and differentiator,” he said. “Because of the rapid pace of change in health care … what's your competitive advantage [as a small hospital]? I think being nimble is one of them. We're a speedboat, not a cruise ship.”

Caroline Hazard, who 100 years ago summoned a community physician to her house to start a cottage hospital, could not have imagined this greatly expanded healthcare system with its leadership in robotic surgery and 1,500 employees connected by the latest technology.

But somehow we get the feeling that she would recognize in that futuristic vision the same Yankee grit and independence that inspired South County Hospital's first trustees in 1919.